Categories

Change Password!

Reset Password!

With the rising demand for patient comfort and ongoing advancements in anesthetic agents, the number of painless outpatient procedures—such as gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopies, bronchoscopies, and hysteroscopies—is steadily rising.

Ciprofol is as effective as propofol for painless hysteroscopy, with slightly longer induction and recovery times but significantly less injection pain and reduced impact on respiratory and circulatory function.

With the rising demand for patient comfort and ongoing advancements in anesthetic agents, the number of painless outpatient procedures—such as gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopies, bronchoscopies, and hysteroscopies—is steadily rising. Improvements in anesthesia technology have notably boosted patient satisfaction and overall comfort. To facilitate pain-free endoscopic procedures, anesthesiologists commonly use a combination of opioid drugs and propofol. Owing to its rapid onset and short duration, propofol remains the preferred sedative for procedures like GI endoscopy and hysteroscopy (uterine cavity examination by endoscopy with access through the cervix).

However, it is fundamental to acknowledge its limitations, including the risk of respiratory depression, hypotension, and bradycardia. Furthermore, a considerable number of patients report pain at the injection site. These concerns underscore the requisition to explore alternative anesthetic agents that offer comparable efficiency with a more favorable safety profile. Ciprofol, a novel short-acting agonist of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor, was approved by the China National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) on 15 Dec 2020, for use in sedation during GI endoscopy procedures. Since its approval, a growing body of research and clinical experience has supported its use in painless endoscopic applications.

In a phase II clinical trial, sedation was successfully attained in all volunteers administered 0.2–0.5 mg/kg of ciprofol for colonoscopy, with all tested doses illustrating favorable safety and tolerability profiles. Moreover, in a comparative study involving general anesthesia for gynecological surgeries, the ciprofol group experienced a markedly lower rate of adverse reactions than those who received propofol (20% vs. 48.33%). Effective sedation and analgesia are fundamental for painless hysteroscopy, as the procedure often triggers prominent discomfort. Given that the induction techniques for anesthesia in hysteroscopy closely mirror those used in painless GI endoscopy, ciprofol emerges as a promising candidate for this setting as well.

Unlike endoscopy, however, hysteroscopy entails intermittent cervical and uterine dilation using dilators, which can arouse intense and fluctuating pain. Managing this variability often requires higher doses of anesthetic agents—raising concerns about complications like hypotension and respiratory depression once the pain stimulus subsides. Therefore, the ideal anesthetic for hysteroscopic procedures must minimize impact on respiratory and cardiovascular function.

Objective

This prospective, randomized, non-inferiority trial sought to explore the sedative efficacy of ciprofol and propofol during painless hysteroscopy. It also aimed to examine its effects on key physiological parameters including blood pressure, respiratory function, and heart rate.

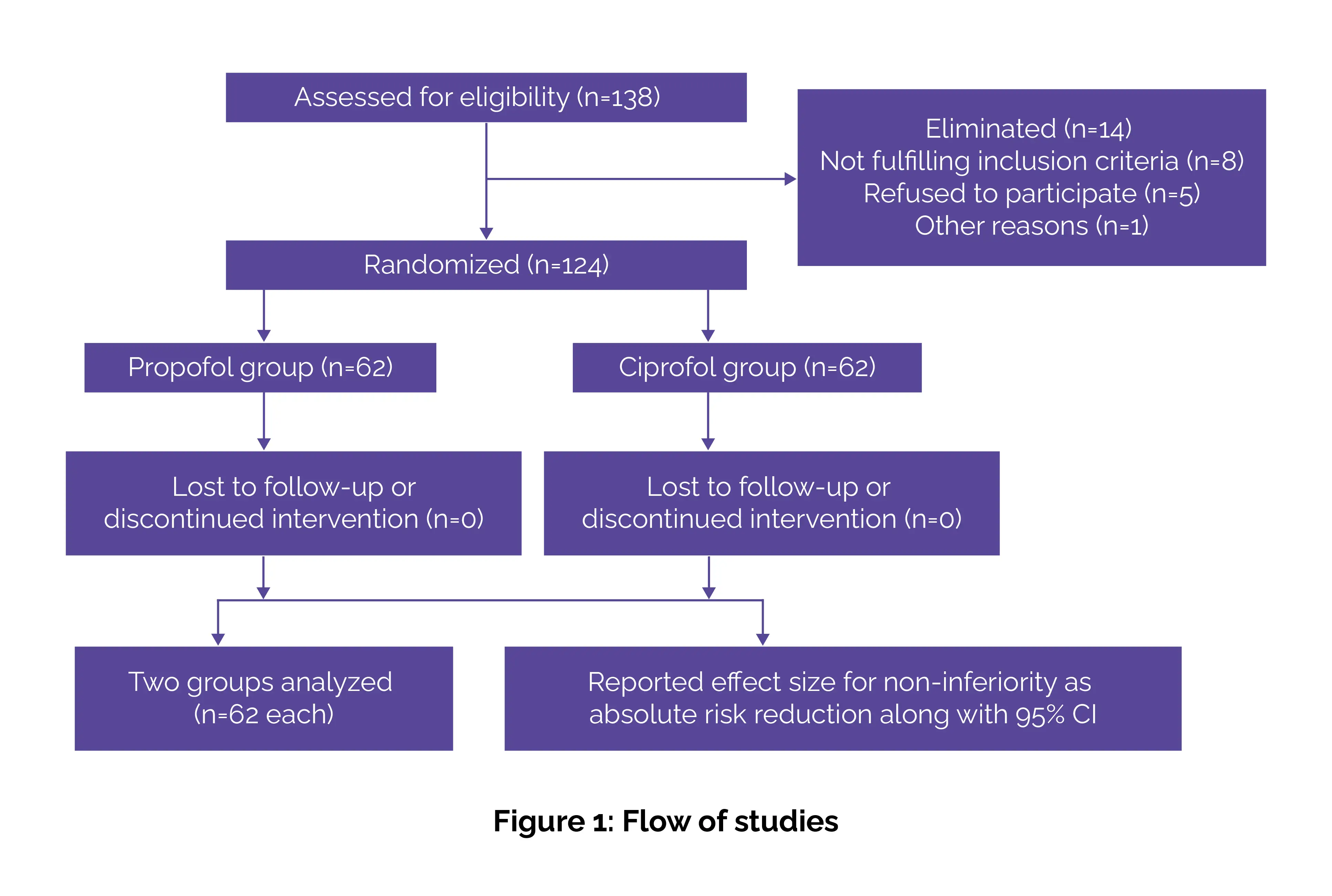

A total of 124 women who were planned to undergo hysteroscopy under total intravenous (IV) anesthesia in the outpatient operating room were recruited.

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

Randomization

Randomization was performed using a number table generated in SPSS 26.0 by an independent anesthesiologist. Group assignments were sealed in numbered envelopes and kept confidential until the study was completed. A nurse who was not involved in data collection or assessment prepared the study drugs. Since both ciprofol and propofol are white emulsions and were coded, the researchers conducting postsurgery follow-up and data analysis remained blinded to the group assignments.

Procedures

Women undergoing hysteroscopy were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to get either ciprofol (0.4 mg/kg) or propofol (2 mg/kg) by IV injection. To keep the study blinded, the volume of both drugs was adjusted with saline to look the same. All patients fasted for over 8 hours and avoided drinking water for at least 2 hours before the procedure. An 18G cannula was placed in the vein on the back of the hand for IV access.

Vital signs, encompassing oxygen saturation (SpO2), blood pressure, and heart rate, were supervised continuously via a multiparameter monitor. Breathing was also monitored using the Capnostream 20p monitor for partial pressure of end-tidal carbon dioxide (PETCO2) and the Integrated Pulmonary Index (IPI), and another device for tidal volume, respiratory rate, and minute ventilation. Before giving the sedative, all patients received 5 μg of sufentanil. For over 30 seconds, ciprofol or propofol was then injected. Sedation was checked every 30 seconds with the help of Modified Observer’s Alertness/Sedation (MOAA/S) scale.

When the score reached ≤1, vaginal disinfection was started. If sedation was not deep enough after 2 minutes, a half-dose was given again over 10 seconds. To maintain sedation, ciprofol was continuously infused at 1–1.5 mg/kg/h and propofol at 5–7 mg/kg/h. If the patient moved, opened their eyes, or spoke, a half-dose was repeated. If more than 5 extra doses were needed within 15 minutes, the sedation was considered unsuccessful, and 1 mg/kg of propofol was given to deepen sedation.

Oxygen was given at 5 L/min through a nasal cannula. If systolic blood pressure dropped below 90 mmHg or more than 30% from baseline, 1–2 mg of dopamine was given. For heart rate under 60 beats per minute, 0.5 mg of atropine was employed. If SpO2 dropped below 90%, the oxygen flow was increased to 10 L/min and the airway was opened. If oxygen levels still didn’t improve, face mask ventilation or a laryngeal mask airway was used.

Study outcomes

Primary outcome

The key outcome was the success rate of painless hysteroscopy. The procedure was deemed unsuccessful if more than 5 supplemental doses of sedative were needed within 15 minutes, prompting the use of propofol for deeper sedation.

Secondary outcomes

Safety measures

Data and statistical analysis

The study's primary endpoint was the success rate of painless hysteroscopy. Non-inferiority was assessed via absolute risk reduction (ARR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI), applying a one-sided type I error rate of 0.025 and a type II error rate of 20%. Sample size was determined based on prior Phase IIb data, assuming a 98% success rate for both groups and allowing a non-inferiority margin of 8%. Accounting for a 20% dropout rate, 124 volunteers (62 per group) were required. Statistical analysis was executed via SPSS 26.0. Continuous data were tested for normality utilizing the Shapiro–Wilk test and assessed visually via Q–Q plots and histograms.

Homogeneity of variance was checked via Levene’s test. If both assumptions were met, data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed with Student’s t-test (or with Welch’s correction when variances were unequal). Non-normally distributed data were checked using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical variables were investigated via the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as suitable. One-sided tests were employed for the primary endpoint, while other comparisons were two-sided. A p-value of ≤0.05 was accounted as statistically significant.

Key findings

Propofol is a commonly used anesthetic agent for both induction and maintenance of general anesthesia due to its rapid onset and quick recovery, making it highly suitable for procedures requiring monitored anesthesia care. Despite these advantages, it is frequently linked with cardiovascular and respiratory depression—manifesting as bradycardia, hypotension, respiratory suppression, and injection-site pain, which affects 25% to 74% of adults. Emerging evidence highlights that intraoperative hypotension markedly escalates the risk of organ injury, particularly to the brain, heart, and kidneys, and is linked to higher mortality rates in high-risk patients.

These safety concerns limit the broader application of propofol in clinical settings. Hence, it is increasingly essential for anesthesiologists to explore alternative sedative agents that can maintain anesthetic efficiency while minimizing hemodynamic instability and improving patient comfort. Ciprofol is a short-acting analog of propofol, belonging to the 2,6-disubstituted phenol class, and acts as a positive modulator of the GABA-A receptor. Previous studies, including a Phase II multicenter trial in those undergoing colonoscopy, have illustrated that ciprofol at doses of 0.4–0.5 mg/kg yields anesthetic effects comparable to 2.0 mg/kg of propofol.

Building on this evidence, the present study applied a comparable dosing regimen but focused on hysteroscopic procedures, which are connected with higher levels of nociceptive stimulation. Beyond reaffirming ciprofol’s comparable efficacy, the study also examined respiratory safety by monitoring parameters such as tidal volume and PETCO2, offering a more comprehensive assessment of its performance during IV anesthesia with preserved spontaneous breathing. Ongoing clinical trials are actively examining ciprofol's efficacy and safety across a range of surgical and diagnostic procedures.

In gynecologic day surgeries, 1 study reported a marginally longer time to loss of consciousness with ciprofol as opposed to propofol, though awakening times remained comparable between groups. Additionally, a meta-analysis of 712 patients revealed no prominent differences between the two agents regarding induction success, time to achieve anesthesia, or time to complete recovery, suggesting that ciprofol offers comprable anesthetic performance to propofol in various clinical settings. In the current trial, the success rate of hysteroscopy carried out under general anesthesia was comparable between the two groups.

However, those receiving ciprofol exhibited a slightly longer induction time—by about 5.6 seconds—and a longer postoperative recovery time—by about 1.5 minutes—as opposed to those given propofol. Two potential factors may explain these differences. First, to maintain blinding during anesthesia induction, ciprofol was diluted with normal saline to match the volume given in the propofol group. This dilution likely lowered the drug’s concentration, contributing to a slower onset. Second, ciprofol’s distinct pharmacokinetics may have played a role.

Due to its higher lipophilicity relative to propofol, ciprofol tends to accumulate more readily in adipose tissue, affecting its distribution and slowing its elimination, which may account for the longer recovery period. These observations are consistent with prior studies, which have reported delayed clearance in lipophilic anesthetic agents due to redistribution phenomena. Despite these differences, ciprofol met the criteria for non-inferiority when compared to propofol, with the lower bound of the 95% CI (−4.28%) remaining within the pre-established margin. Additionally, no prominent difference was noted between the two groups in terms of delayed awakening.

Overall, the slight prolongation in both induction and recovery times with ciprofol appears clinically acceptable in most practice settings. Respiratory and circulatory suppression remains a well-recognized limitation of propofol. In a study by Man et al., those receiving propofol during gynecological procedures experienced more pronounced reductions in blood pressure and heart rate when compared to those given ciprofol. Similarly, a meta-analysis highlighted a lower incidence of hypotension in the ciprofol group during anesthesia induction.

In contrast, Peng's study revealed comparable trends in blood pressure, heart rate, and SpO2 fluctuations between the two drugs, with no vital differences observed during induction and intraoperative recovery phases. In the current study, subjects in the ciprofol group exhibited higher diastolic blood pressure, minute ventilation, SpO2, and minimum SpO2 values post-induction than those in the propofol group. However, the rates of hypotension, bradycardia, and hypoxia were not considerably different between the study groups. While those without pre-existing health issues may tolerate mild respiratory and circulatory depression without complications, those with underlying cardiopulmonary or cerebrovascular conditions are more prone to perioperative hypoxia or adverse events due to anesthetic-induced hemodynamic changes.

Furthermore, when the pain stimulus from hysteroscopy diminishes, previously administered anesthetic doses may induce a drop in oxygen saturation. The higher minimum SpO2 seen with ciprofol suggests it may be a safer option for high-risk people undergoing painless hysteroscopy, but further research is needed to confirm this. Injection pain is another long-standing concern with propofol. Reported incidence rates reach 45.1%, while ciprofol exhibits a substantially lower rate of 8.8%. This difference is largely attributed to ciprofol’s distinct chemical structure and lower lipophilicity, which promote stronger binding to GABA-A receptors and result in reduced free plasma concentrations—ultimately leading to less pain upon injection.

The findings were consistent with earlier research: 41.935% of patients in the propofol group experienced injection pain during induction, compared to just 1.613% in the ciprofol group. Importantly, no vital differences were noted in the IPI between the two groups following anesthesia. Despite minor variations in oxygen saturation—averaging 98.39% in the ciprofol group and 97.25% in the propofol group—values remained within the normal range. There were also no notable differences in PETCO2 or respiratory rate.

These consistent respiratory parameters contributed to similar IPI scores across both groups, all exceeding a threshold of 8, suggesting that no additional respiratory support was necessary for either group. Future research is planned to:

Ciprofol provides comparable sedation efficacy to propofol for painless hysteroscopy, with significantly less injection pain and better respiratory and circulatory stability. Although it has slightly longer induction and recovery times, its improved safety profile makes it a promising alternative to propofol in outpatient gynecologic procedures.

Annals of Medicine

Efficacy and safety of ciprofol for sedation/anesthesia in patients undergoing hysteroscopy: a prospective, randomized, non-inferiority trial

Shi Cheng et al.

Comments (0)