Categories

Change Password!

Reset Password!

This case report presents a 35-year-old Aboriginal male who attended a general practice for a routine Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health check. During the consultation, he reported experiencing nocturnal restlessness in his legs. Though he did not complain of tiredness, weakness, or any systemic symptoms commonly associated with anaemia, blood tests surprisingly revealed severe iron deficiency anemia (IDA) and dyslipidaemia.

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation and diagnostic findings, a diagnosis of restless legs syndrome (RLS) secondary to IDA was made. Treatment was initiated with iron supplementation. Following iron replacement therapy, the patient’s RLS symptoms markedly improved, emphasizing the importance of screening for secondary causes such as IDA in those presenting with symptoms of RLS, even in the absence of classic anaemia symptoms. This case reinforces the need for a thorough investigation of potentially reversible causes in RLS.

Introduction

Leg pain, including restless legs, is one of the most prevalent complaints seen in general practices. RLS (also known as Willis-Ekbom disease, WED) is a frequently overlooked yet disruptive neurological ailment that profoundly affects sleep quality and overall well-being. This sensorimotor disorder of the nervous system affects around 10% of the population, with an even higher prevalence among those with end-stage renal disease. While a strong connection exists between reduced peripheral iron levels and the heightened risk and severity of RLS, its exact prevalence and clinical implications in IDA sufferers remain underexplored.

The condition may arise spontaneously (idiopathic) or be triggered by underlying factors such as iron deficiency, pregnancy, advanced renal disease, or the use of certain medications—particularly antidepressants and antihistamines like prochlorperazine, metoclopramide, fluoxetine, sertraline, and mirtazapine. Other contributors encompass neuroleptic antidopaminergic agents, alcohol, caffeine, lithium, and beta-blockers, all of which may disrupt dopaminergic pathways and provoke RLS symptoms.

The underlying mechanisms of RLS remain only partially unraveled. In most idiopathic cases, the ailment appears to stem from impaired dopaminergic signaling and reduced brain iron availability. A familial trend—often autosomal dominant—further hints at a genetic foundation. In uremic RLS, factors such as IDA, subtle shifts in electrolytes (calcium, phosphate, potassium), and early peripheral neuropathy may play a role. Emerging genetic links, particularly polymorphisms in BTBD9 and MEIS1, strengthen the case for a hereditary component.

Notably, pregnancy—especially the third trimester—frequently brings RLS to the forefront, suggesting hormonal and metabolic shifts may also contribute. RLS sufferers often experience an intense urge to move their legs due to uncomfortable or even painful sensations. These sensations are variably described as creeping, crawling, itching, burning, searing, tugging, pulling, aching, electric, hot or cold, or simply “restless.” While it's uncommon for symptoms to be isolated to the arms, around half of those affected report involvement of both arms and legs. Symptoms typically emerge during periods of rest—especially when lying down—and can persist for several minutes to over an hour.

Although less common, episodes may also occur while sitting quietly, such as during long meetings or travel. Symptoms tend to worsen when the body is inactive and the mind is at ease, becoming more intense in the evening and early morning hours. In severe cases, this daily rhythm may be disrupted entirely. External factors such as shift work, certain medications, and coexisting sleep disorders may further influence symptom patterns. Fortunately, most cases are mild and don’t warrant medical intervention.

Diagnosing RLS relies chiefly on clinical evaluation, supported by the exclusion of alternative causes through detailed history-taking and laboratory assessments. For those with mild RLS symptoms, non-pharmacological approaches are often effective. Lifestyle modifications like following a healthy eating plan, engaging in regular workouts, and maintaining good sleep hygiene are commonly advised. Identifying and correcting iron deficiency is crucial, as low iron levels can trigger or intensify RLS symptoms. When deficiency is confirmed, iron supplementation must aim to raise serum ferritin levels to at least 50 μg/L. Oral iron therapy typically involves ferrous fumarate at a dose of 200 mg (providing 67.5 mg of elemental iron) twice daily.

Medical History

The patient denied experiencing any daytime symptoms such as tiredness, general weakness, shortness of breath, loss of appetite, and gastrointestinal complaints (e.g., nausea, vomiting, or abdominal discomfort). He also reported no symptoms indicative of obstructive sleep apnoea, such as loud snoring, choking, or gasping during sleep.

Regarding his dietary habits, the patient did not consume red meat, and his intake of fruits was notably minimal, which may have contributed to potential nutritional deficiencies. In his family history, there were no signs of IDA or gastrointestinal diseases. However, there was a significant family history of diabetes and cardiovascular conditions, suggesting a genetic predisposition to metabolic and heart-related issues.

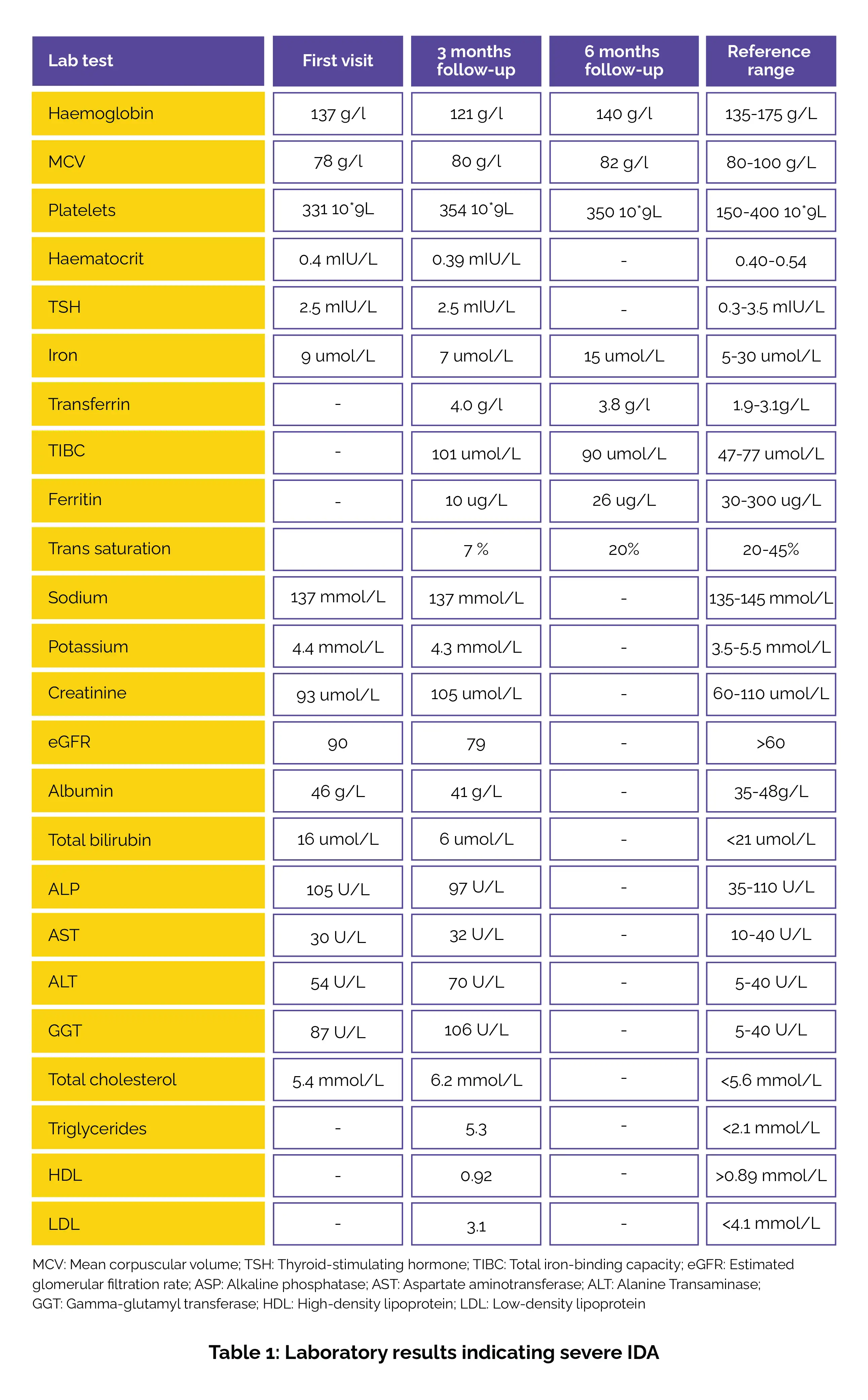

On initial examination, the patient’s vital signs included a blood pressure of 114/72 mmHg, a heart rate of 82 beats per minute, and a body mass index of 26.5, placing him in the overweight range. His neurological examination was unremarkable. The patient was educated about the possible secondary causes of his leg discomfort, which might be contributing to his symptoms of restlessness. Laboratory results on the first visit showed severe IDA, with a ferritin level of 10 µg/L (well below the normal range), haemoglobin of 121 g/L (low), and MCV of 80 g/L (borderline microcytic).

Iron studies revealed low serum iron (9 µmol/L) and a transferrin saturation of just 7%, both indicating a significant iron deficiency. Elevated transferrin (4.0 g/L) and TIBC at 101 µmol/L further confirmed the deficiency. The patient also presented with moderate dyslipidaemia, with total cholesterol at 6.2 mmol/L (elevated), triglycerides at 5.3 mmol/L (elevated), and low HDL at 0.92 mmol/L, which are risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Regarding liver and renal function, his liver enzymes were elevated with ALT at 70 U/L (normal <40 U/L), AST at 32 U/L (normal <40 U/L), and GGT at 106 U/L (normal <40 U/L), suggesting possible liver dysfunction. An abdominal ultrasound confirmed a diagnosis of fatty liver. Renal function was relatively stable, with an eGFR of 79 (still within the normal range of >60) and creatinine at 105 µmol/L, which was within the reference range (60-110 µmol/L). His coeliac antibodies were found to be negative, and vitamin B12 was normal, as shown in Table 1:

Following IDA confirmation, the patient was initiated on oral iron replacement therapy. He was prescribed 200 mg ferrous fumarate (967.5 mg) to be taken twice daily. In addition to pharmacologic treatment, he was counseled on dietary modifications. He was advised to increase his intake of iron-rich foods such as red meat, fruits, and green leafy vegetables. The patient was scheduled for routine follow-up visits to monitor his progress and blood test results.

At follow-up, after 6 months of treatment, his ferritin level improved to 26 µg/L and his haemoglobin level normalized to 140 g/L (within the normal range of 135-175 g/L). His iron levels also increased to 15 µmol/L. Although dyslipidaemia persisted, with total cholesterol still at 6.2 mmol/L, the patient's IDA showed prominent improvement over the 6-month period.

Discussion

RLS is marked by an irresistible urge to move the legs, often accompanied by sensations ranging from crawling to burning, predominantly in the lower limbs. These symptoms typically deteriorate during rest, especially at night. Its pathogenesis is complex and continuously evolving. Managing RLS effectively hinges on an accurate diagnosis, emphasizing the prominent role of healthcare professionals in patient care. Identifying reversible causes and considering non-pharmacological interventions—such as iron supplementation (oral or intravenous)—are key to treatment.

Pharmacological options are also available, with low-dose dopamine agonists historically serving as the go-to treatment for RLS/WED. Iron deficiency affects roughly 25% of RLS patients. For those with low to normal serum ferritin levels (15-75 ng/ml), oral iron therapy yields symptom relief. For individuals with ferritin levels below 75 ng/ml, ferrous sulfate (325 mg daily) or ferrous fumarate (200 mg, providing 67.5 mg of iron, twice daily) is advocated, ideally with vitamin C to boost absorption. Some patients may require intravenous iron if they cannot tolerate oral supplements or if idiopathic RLS is unresponsive, though intravenous iron carries a risk of anaphylaxis and must be prudently used.

For healthcare providers, RLS presents a key challenge due to the incomplete grasp of its underlying pathophysiology. Diagnosis and treatment can be complex, and patients should be advised to steer clear of medications known to trigger or worsen symptoms. For those with chronic kidney disease or those undergoing dialysis, regular monitoring is fundamental, along with managing electrolyte imbalances and supplementing vitamin D in cases of deficiency. While a variety of therapies exist for RLS, healthcare team must be cautious, especially when using dopaminergic therapies, as they can often lead to symptom augmentation over time.

Dopamine agonists such as cabergoline, pramipexole, ropinirole, and rotigotine have been shown to ameliorate symptoms, improve sleep, and boost overall quality of life. However, medications like pramipexole and ropinirole come with the risk of deleterious effects such as gambling addiction and notable weight gain. Contrarily, the rotigotine transdermal patch is a more tolerable option with a lower risk of symptom aggravation. Ultimately, it’s essential to rule out underlying causes such as IDA, kidney failure, medication-triggered electrolyte imbalances, and pregnancy before diagnosing RLS. This responsibility underscores the necessity of a comprehensive, thoughtful approach to patient care.

Learning

Cureus

Restless Legs Syndrome Secondary to Iron Deficiency Anaemia: A Case Report

Amresh Gul et al.

Comments (0)